Bunnings was packed on March 22, 2020. The first Melbourne lockdown had just been announced, but no-one knew what it meant yet. We’d watched the residents of Wuhan get locked in their apartments, and it looked like we were next. People wanted to make sure that no matter what, they’d have some home-grown broccoli, cabbage, snow peas.

The winter vegetable seedlings were all snapped up by the time I arrived, but I managed to grab some seeds, a seed starter kit, and a few fresh herbs: parsley, thyme, rosemary, chives, and a big peppermint plant. I could make lockdown mojitos. In the checkout line, I heard someone say there’d been a run on the liquor stores - it wasn’t till the following day that the government clarified that alcohol was an essential good. The bottle-os would remain open.

Between my herbs and the office plants I rescued, I wound up with so many pots I needed new shelves. I liked having something green in my living room, now my home office. I was spending 90% of my waking hours in one room.

A fly in the ointment

Soon that room was filled with fungus gnats. Have you ever met a fungus gnat? It’s an inoffensive creature, a tiny fly that drifts in a meandering, drunken course around the room. It doesn’t make a sound. It looks like a miniature mosquito, but it doesn’t bite. One fungus gnat would be fine. I had about a hundred.

Fungus gnat larvae live in soil, where they eat rotting material. They thrive in damp conditions so they’re usually a problem when you overwater your plants. I tried drying out the soil, but it didn’t seem to work; there were as many as ever.

Fungus gnats don’t usually harm plants. If you have a serious infestation they may damage the roots, but mostly they coexist. I was the one who couldn’t coexist with them. They’d waft into my face as I was trying to work. It drove me nuts.

I looked up how to kill them. Pesticides work to some extent, but the gnats have a fast life cycle and quickly evolve resistance. Plus I wanted to eat most of my plants, and I wasn’t keen on eating pesticides. You can use less toxic stuff like neem oil, but Bunnings was sold out of it online - supply chain problems.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly

Googling “how to kill fungus gnats” yielded an intriguing alternative: beneficial predatory organisms. Set a spider to catch a fly.

Working from home was dull, so I thought, why not?1 There are companies that will send you live predators by post. Two predators of fungus gnats were available online: nematodes and hypoaspis mites. The mites were marginally cheaper. I’d also considered parasitic wasps, because when all else is equal I prefer the weirdest possible solution. Unfortunately parasitic wasps are more specialised; they would only control fungus gnats, nothing else. Hypoaspis also eat thrips and other soil-dwelling pests besides fungus gnats, so they’re better value for money.

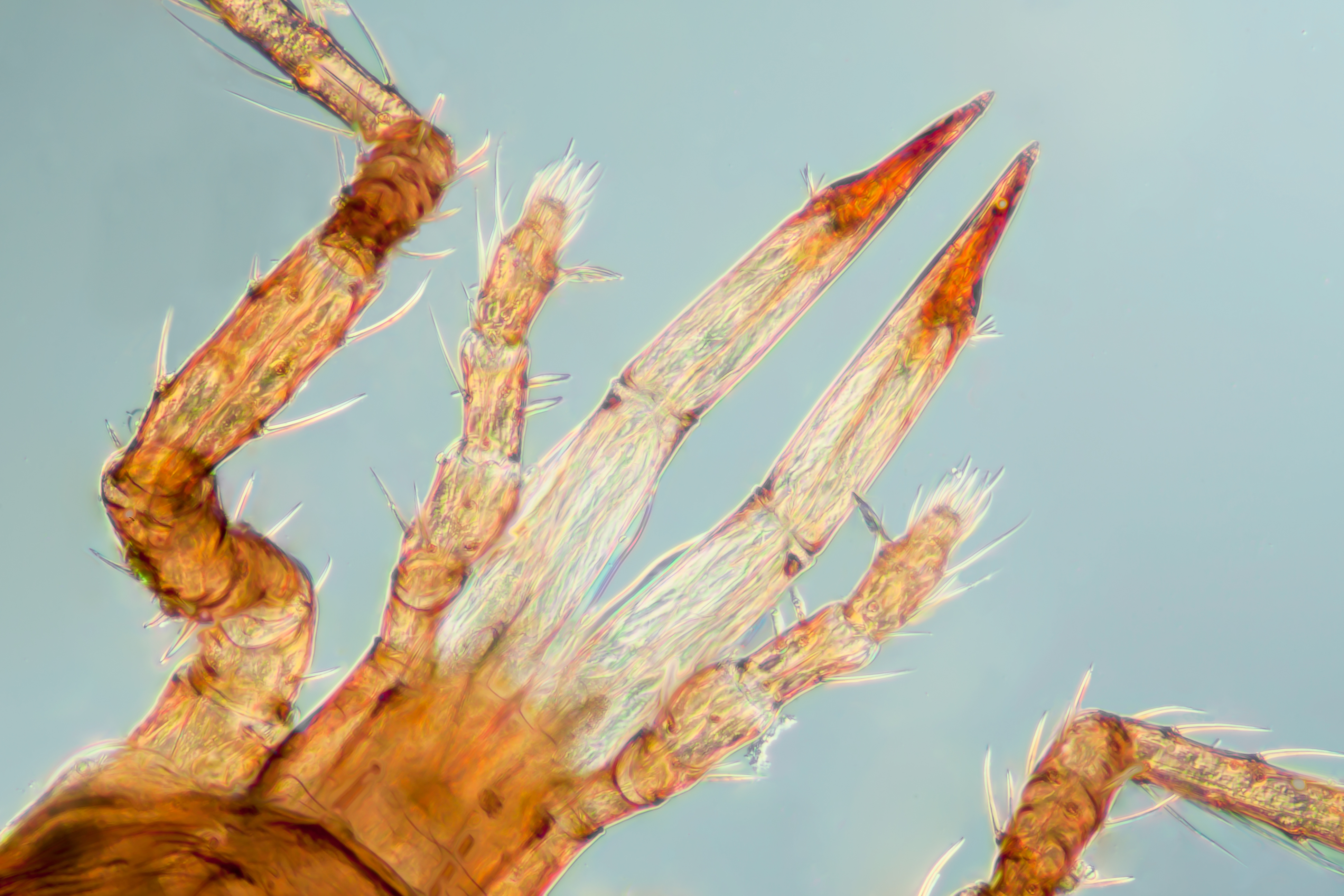

Hypoaspis mites are only half a millimeter long. They live on soil and eat fungus gnat larvae. It takes them a while to work because you have to wait for all the adult gnats to die off. They were a little more expensive than pesticide, but I’d only have to buy them once, and then they’d reproduce and keep my gnats at bay indefinitely. It was the sustainable solution. And I didn’t have to worry about eating pesticides … only mites. So on May 16 I ordered the minimum quantity of hypoaspis (that’s 15,000 mites!) from Bioworks Australia.

The mites were delivered by Toll Group. The package was supposed to ship fast because it contained living organisms, but delivery was delayed. Everyone was ordering packages online, increasing demand, and the government had imposed staff density limits on business, reducing capacity. Every mail carrier was overwhelmed. When my mites finally arrived, Toll knocked on my door obnoxiously early and I missed them. The next day, May 22, I set an alarm and caught them.

The mites were shipped in a plastic jar full of coconut fibre, with air holes in the lid. I spooned the coir around the roots of my plants, watching the tiny white dots crawling over it. Soon, I thought, as I swatted a gnat out of my face.

More mites, more problems

The fungus gnats started to decline, but my plants weren’t thriving. They were gradually becoming sickly. Tiny pale spots were appearing on the mint leaves, like the green part of the leaf had died, leaving a patch of leaf skeleton.

Again I thought maybe I was overwatering - or underwatering - or alternating between the two. Overwatering and underwatering produce almost identical symptoms: overwatering makes the roots rot, so the plant takes up less water and dries out, just like it would dry out when underwatered. But the soil felt good; a tiny bit moist but not too much. I tried misting the leaves to no avail.

I watched my ailing plants with the sort of focused interest you get in the time of COVID when you have absolutely nothing else to look at, day in, day out. The hypoaspis were still running purposefully around in the soil. A few little jumping spiders had found their way indoors and were hopping around, leaving stray strands of silk on the leaves. Those spiders and mites were the closest thing I had to pets.

The spider silk was growing thicker. Suspiciously thick. On June 6 I looked closer and realised it was crawling with tiny dots, even smaller than hypoaspis. I remembered I’d heard the term “spider mites”, googled it, and that was it: that was my problem.

Where did the spider mites come from? When I tell this story, people tend to assume the spider mites hitched a ride with the hypoaspis, as if all mites must be friends with each other somehow. That seems unlikely. Hypoaspis lives in soil whereas spider mites live on leaves and green stems. There’s no way to know, but it seems more likely that they just came in from the garden the same way my jumping spiders did. Or they could have been on the seedlings when I bought them from Bunnings. Classic tragedy, the disaster baked into the story from the start.

Spider mites, unlike hypoaspis, are vegetarian. They latch onto your plants and suck the sap out of them. They thrive in indoor gardens thanks to the lack of predators and the controlled temperature. Absent any population control, the infestation will grow exponentially until it kills the plants. I had to do something.

I thought about pesticides again. However, spider mites have an obscenely fast life cycle and evolve resistance to common pesticides quickly. Also, pesticides would kill my beloved hypoaspis mites. Having started down the road of biological control I was now committed to it.

Bioworks had a predator available for spider mites: persimilis. They were almost twice the price of hypoaspis but they seemed to be my only option. I put in the minimum order: a bucket of 4,000 persimilis mites.

The bell tolls again

Once again, Toll knocked on my door obscenely early and I missed the delivery. I’d asked them to leave the package by the door but they ignored me. I wasn’t worried; I’d gone through this before. I set an alarm for the next morning. Tracking info said delivery was rescheduled for the next day. But the next day came and went with no delivery. A week later, without warning, they tried again and I missed them again.

Toll left these little “sorry we missed you” cards, which said I could manage my delivery via a mytoll webpage. The page didn’t load. It took another week and a long phone call to Toll to figure out there were multiple package-managing pages, and only one of them actually worked. I finally managed to make them deliver to a local newsagent I could pick up from. It got there June 29. My persimilis mites had been in transit for three weeks.

In the meantime, the spider mites had been hard at work, slowly killing my plants. The mint had started to take on that filigreed look that dead leaves get, when the green rots away, leaving the intricate leaf skeleton behind.

I went to pick my persimilis mites up on June 30, 2020. That day, Melbourne recorded 75 new cases of covid, and the Vic state government announced that in two days’ time, on July 2, they would lock down 10 postcodes in a futile attempt to stem the tide of our second wave of COVID. Cases were popping up everywhere. I remember ranting to my friends at the time: “They should be locking down the whole city. They’re trying to use a scalpel when they need to use a cleaver.” Full lockdown started a week later, a delay that cost lives.

I walked into the newsagent wearing a mask that felt totally inadequate to the risk. It was a cloth mask; I still felt like I shouldn’t buy surgical ones, like surely medical professionals needed them more, some holdover guilt from the days when supply really was desperate. Still, I’d sewn some wire across the nose bridge so the fit was ok.

It’s all in the delivery

The newsagent guy took my driver’s license, found my package, and started typing something on his computer. There was a long pause. He turned back to me.

“I’m afraid I can’t release this to you.”

“Huh? Why not?”

He gestured to a row of laminated barcodes taped to the counter - one was marked ‘Toll’, another ‘FedEx’. He poked the Toll card.

“The delivery guy hasn’t scanned this barcode to show that he dropped it off. There’s no record of it being here in the system, so I can’t record that I’ve released it to you.”

“But it’s my package. It’s got my name and address on it, you’ve seen my ID, it’s mine. And I’m right here. Why can’t you hand over a package that is obviously mine?”

“Toll wouldn’t know that it had been delivered to you. It’s more than my job is worth.”

“So what has to happen for you to release the package to me?”

“The delivery guy has to come back and scan the barcode.”

“Does he come in every day?”

“Not every day. Might be a few days. You can call Toll and find out.”

The thought of another long phone conversation with Toll made my heart sink. I eyed the package. He’d set it down on the other side of the counter, but it was within lunging distance…

“I could just grab that package and run. It wouldn’t be your fault.”

“I’d be very happy if you did that.” But he gently slid the package out of reach. “You’re going to have to call Toll.”

I called Toll. It took forever to reach a human. When I did, the lady had a lot of questions for me, and another lot of questions for the newsagent guy. I put the phone on speaker so she could ask him for barcodes, tracking numbers, his name, the address of the newsagent. He was a champion multitasker, serving other customers while answering her.

The newsagent was starting to fill up, and I was excruciatingly aware that I wasn’t quite maintaining a 1.5m distance from other humans. I could feel little drafts as air leaked around the edges of my mask. Toll put me on hold for ten minutes, which I spent hovering awkwardly by the drinks fridge.

I chatted to the newsagent guy, who told me that this sort of thing happened occasionally with other mail carriers, but regularly with Toll. In his experience, Toll was the absolute worst.

The Toll lady came back and said, “We’re going to have to send that package back to the depot so it can be redelivered to you.”

“Oh no. No. This package has already been delayed for weeks! It’s obviously mine, and I’m right here. Why can’t I just collect it now?”

“I’m sorry. There’s nothing I can do. It has to go back to the depot.”

I said, “I can’t afford another week’s delay. This package contains living organisms which may all now be dead.”

She said, “Ah.” Then she said, “Let me talk to my manager.” And put me on hold for another ten minutes. I went back to hovering by the drinks fridge.

Eventually she came back: “My manager says you can collect the package.”

I put her on speaker phone so the newsagent guy could hear. I made her say it again. I said, “And it’s ok for this guy to release the package? He’s not gonna get in trouble because you have no record of the package being here?”

“No. He’ll be fine. I’ll take care of it on our end.”

I took my package, thanked the longsuffering newsagent guy for his patience, adjusted my breath-soaked mask, and went home. I pulled out scissors and finally opened the package.

All the mites were dead.

Second time’s the charm

The persimilis mites had been shipped in a bucket of fresh green leaves, which had rotted in transit. Tiny brown dots covered the sides of the bucket, each spot marking a mouldy mite corpse.

I called BioWorks and explained the situation. I sent them this photo of my poor expired mites. They were very understanding; they could see the tracking information and understood my pain. They said they’d send me another batch of mites.

I asked, “Is there any chance they can be shipped not with Toll?”

They said, “Well, Toll really is the best.”

After a little more persuasion BioWorks agreed to go with Australia post. I asked for advice on how to keep my plants going while I was waiting for the predators to arrive. They suggested I could mist the plants to replace some lost moisture, and if I had the energy, I could wipe down the leaves to remove some of the spider mites. I misted almost everything.

Not everything. The mint was an absolute goner; the leaves were dead, the stems were dead. I thought I should clean out the pot for reuse but I found I didn’t have the energy, so I just put it out in the courtyard and left it for dead.

The following day, July 1, I looked up and realised I hadn’t seen a fungus gnat in days. It had been four weeks since I applied the hypoaspis mites, and they had worked. There were no more miniature flies getting in my face. When I looked at the plants close up, I could still see many little hypoaspis mites running over the soil, keeping me safe from future infestation.

It was such a pity that everything was now suffering from spider mites.

Australia post took a week to deliver the second batch of persimilis, but when they arrived on July 10 they were alive; bright little orange spots running over the green leaves. I distributed the leaves around the base of each plant, watching the tiny orange predators start exploring their new home. Soon, I thought.

Boom and bust

I watched as the spider mite population slowly dwindled over the next few weeks. The herbs started thriving again, putting out new leaves unblemished by spider mite bites.

In the same time period, Melbourne’s second wave was rising. On July 9, the day before my second batch of persimilis arrived, we had 165 covid cases and the state government belatedly locked down the whole city. But even under lockdown the numbers kept rising. The government didn’t introduce a mask mandate until July 23, when we had 403 cases. There was still some ridiculous debate about whether masks made a difference. On August 2, we recorded 671 cases and the government imposed a curfew. After that, case numbers declined steadily, but they took until October 31 to drop to zero and stay there.

At the end of August, still living under curfew, I looked at my plants and noticed something troubling: I could no longer see any persimilis mites running over my plants’ leaves. Looking at the potting mix, I couldn’t see any hypoaspis, either. The predators protecting my crop were gone.

I had imagined that predatory beneficials were a sustainable solution: apply them once, then reap the benefits forever. I now realised what should have been obvious from the start: predators will only survive while their prey is available. I had applied 15,000 hypoaspis and 4,000 persimilis to my plants, enough to eat every single fungus gnat and spider mite. After the prey were gone, the predators had starved to death.

If another spider mite or fungus gnat made its way in from the garden, I’d have to go through the whole ordeal again. Or admit defeat and use pesticides.

Or grow my own predators. After all, there must be a way that BioWorks managed to do it …

Meet Prof Felix Wäckers

I began searching for alternative foods for predatory mites. Somehow I stumbled across a slide deck made by Professor Felix Wäckers. I can’t find the PDF now. It’s been 11 months since I read it, so it’s dropped out of my browser history, and I failed to save it, which is sad because it felt like a revelation. I learned more from that one weird PDF than I had in the four previous months. In the process of searching for it I think I’ve found every other slide deck Wäckers ever released, and I now feel I should introduce him.

Felix Wäckers researches biological control of pests. He is a professor at Lancaster University and is director of R&D at Biobest. He writes papers with titles like “Quest for the Allmitey”. He never fully smiles in photos.

Wäckers’ Powerpoint style has a certain je ne sais quoi. Here is how he explains that farmers should use tools:

One of the tools Wäckers has developed is Nutrimite. Here’s the slide on Nutrimite from Biobest’s knowledge and training center. The PDF doesn’t have Wäckers’ name on it, but you can tell he made this slide from how the text has been pasted directly onto the photo.

Slide text:

Nutrimite!

What?

- highly nutritional food supplement based on specially selected pollen

Aim?

- a booster for pollen feeding predatory mites

- to accelerate and enhance population development

- to help existing populations survive periods of low prey density

Nutrimite was exactly what I was looking for: something I could feed to my beneficial mites, to keep them around in case a pest showed up. It’s made of Typha pollen. Typha are cattails, sometimes also called bullrushes (although not all plants called ‘bullrushes’ are Typha).

Predatory mites have evolved in environments where prey availability fluctuates. They can absolutely survive on alternative food sources - especially pollen. Not all pollen is created equal; some types of pollen are actually toxic to the mites, and other kinds nourish the pest species too. You’ve got to choose the right pollen for the job. Biobest chose Typha because it avoids these disadvantages.

Here’s how Wäckers shows we should rethink the idea of feeding predators.

I remember particularly enjoying a slide with the quote, “BUILD UP THE ARMY BEFORE THE ENEMY ARRIVES”. I can’t find that exact slide now, but Wäckers has said similar things in interviews. It makes sense: if you feed your persimilis well, you’ll never have to worry about spider mites establishing a population.

Ecological implications

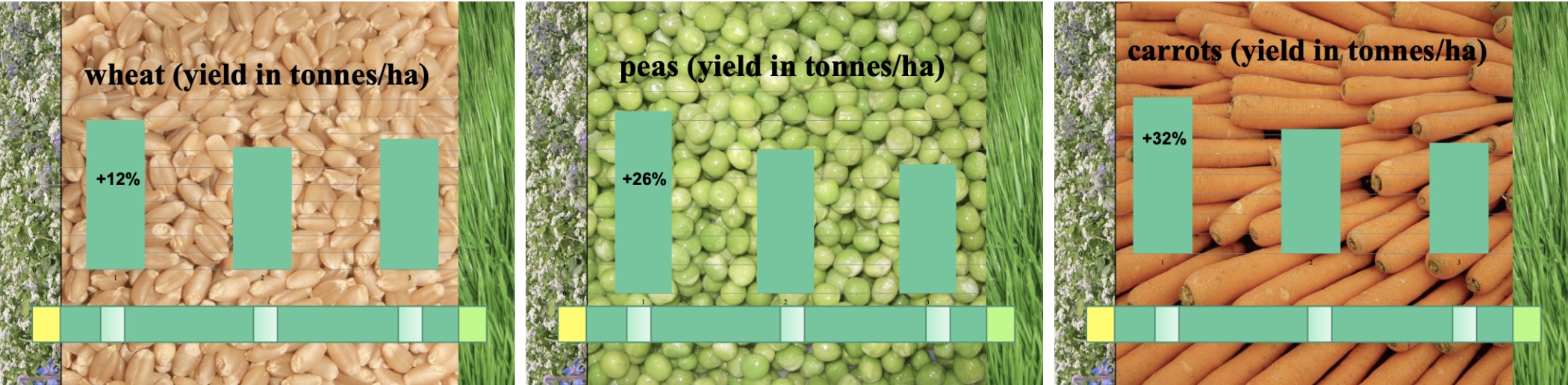

Wäckers further explains that when farmers plant wildflowers in field margins, they support small populations of beneficial predatory organisms, which can leap into action if a pest establishes itself on the main crop. There’s no actual conflict between biodiversity and productivity. Fields with flowering margins produced more crops than fields without.

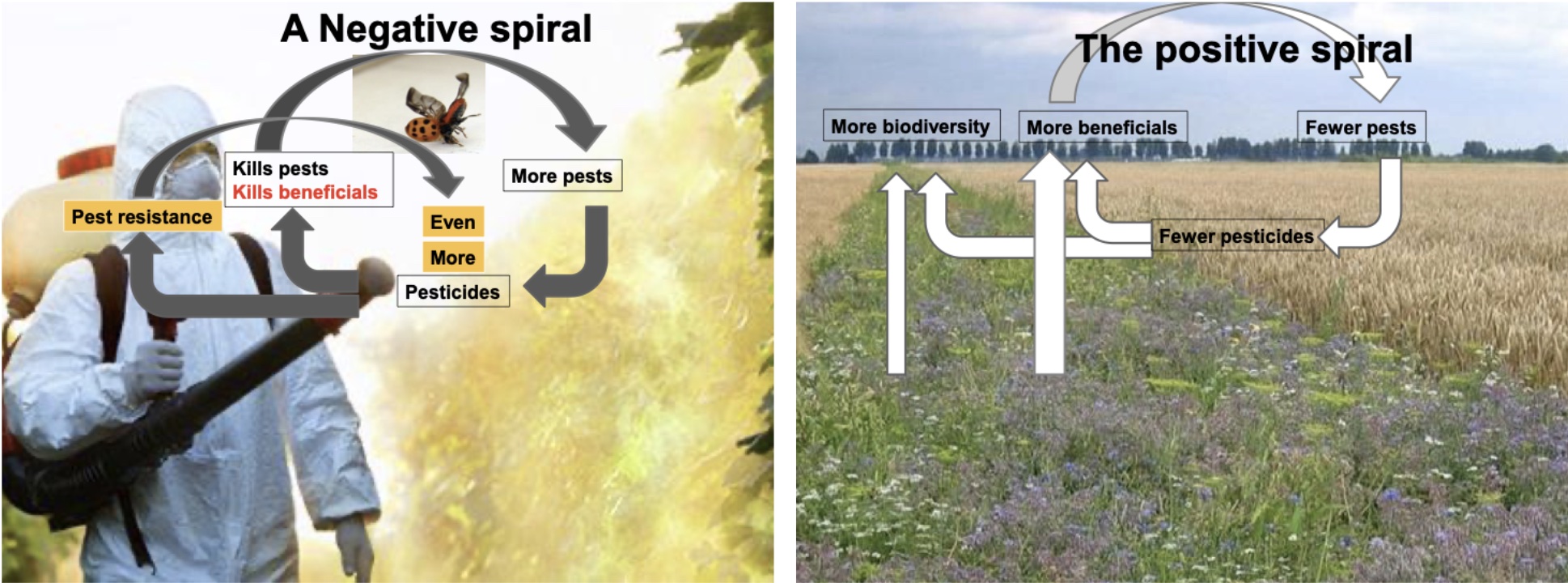

Supporting a population of beneficials allows farmers to avoid pesticide use - what I’d been aiming for all along. They allow farmers to escape from a negative spiral, in which pesticides kill pests and beneficials alike, and pest resistance requires the use of ever more toxic pesticides. Instead we can enter the positive spiral in which biodiversity encourages beneficials, which reduce the pest populations.

In my indoor space, I had created a tiny ecosystem, mostly cut off from the garden outside. Once a pest got in, it was able to grow exponentially thanks to the lack of natural predators. Farm monocultures have similar problems. A little pollen in the field margins gives the predators a foothold, and can soften the volatile booms and busts of predator-prey populations.

At this point I looked out the window and realised that my mint wasn’t dead after all. After being eaten down to the soil, it had started sprouting again from the roots. The spider mites were gone. They might have died of cold, or of starvation because they’d completely finished the mint, but I like to think that when I put that pot outside, some beneficial bug found the spider mites and started snacking on them.

Good afternoon, good evening, and good mite

In a greenhouse or a home office, Nutrimite can support predatory mites. Sadly, however, I couldn’t order a tub of Nutrimite as easily as I could order a tub of mites. Biobest is based in Belgium and doesn’t offer retail quantities, catering instead to farmers. But there’s another source of pollen: flowering plants. I just need to find some cattails, shake the pollen off them, and I’ll be set.

Here’s where this chapter ends. I haven’t found any flowering cattails, so I haven’t yet had a chance to try the next natural experiment. I’ve also moved house and given away all my plants, which is another story altogether. In any case my beneficial mites had pretty much died out by the time I realised I needed pollen. I hope there will be another chapter of this story when I have plants again, order mites again, argue with Toll again, and build up my army of good mites by feeding them pollen. Sounds crazy, but it just mite work.

-

After all, it’s not like biological pest control has ever had negative consequences … ↩